Developer Led GTM

Dismantling developer focused orgs from scratch.

Setting the Scene

If the newsletter is called Developer Led and this piece is titled Developer Led GTM, it’s reasonable to assume I’m introducing a proprietary framework or some branded methodology.

I’m not.

My perspective comes from a different place. I started my career as a software engineer working in devtools. I haven’t been a full-time engineer for years, but I still write code every day (with and without AI). Most people in developer marketing or technical product marketing will tell you that you should, even if you didn’t start in engineering. The reason is simple:

You can’t build, market, or sell to developers without understanding how they think.

Over time I noticed a pattern in the teams and companies that consistently got developer-facing products right. They all had the same backbone:

(ex-)developers marketing and selling developer tools to developers.

Realizing this felt less like inventing a system and more like uncovering an obvious truth that had been sitting in plain sight.

I could have called this model developer-focused, but that doesn’t quite capture it.

Developer Led does.

The Product is Everything

My thinking around developer products shifted when I stopped treating “the product” as just the SDK, API, or managed platform. When most people hear devtool, they picture the technical surface: the endpoint, the library, the CLI. The thing developers use to build.

But that’s only one slice.

Your product is everything a developer touches or sees before they ever write a line of code.

Your website and every subpage. Your docs. Tutorials, samples, guides. Your SDKs and APIs. Social channels. Case studies. Release notes. Even the information architecture that connects it all.

If any part of that surface area is confusing, incomplete, or forces someone to leave your ecosystem to search elsewhere, that’s a product failure not a marketing one.

I think of it as the “product OS.” Once a developer enters, they should be able to navigate, explore, learn, build, and decide without friction. The packaging matters as much as the underlying capability. In many cases, more.

This perspective doesn’t match most GTM playbooks, and that’s intentional. The goal is to expand how we think about developer products and to give you a reason to reconsider how your own product, packaging, and go-to-market model fit together. In this one, your product OS is your GTM. You start thinking about things as a whole.

A Shared Model

Before going deeper, it’s helpful to establish the foundation for how developers move through a product. People in the devtools space like to call it a journey, and in this case the term fits.

Here’s the sequence I use:

Awareness → Interest → Purchase → Building (Activation) → Advocacy

This isn’t a marketing funnel. It’s the path a developer with zero prior context must follow to become confident, ship something real, and eventually talk about the product publicly. Every part of your GTM strategy is anchored to how well you support this progression.

For this piece, I’m focusing entirely on the developer-first model. I’m not covering the developer-plus one here.

Developer Led GTM

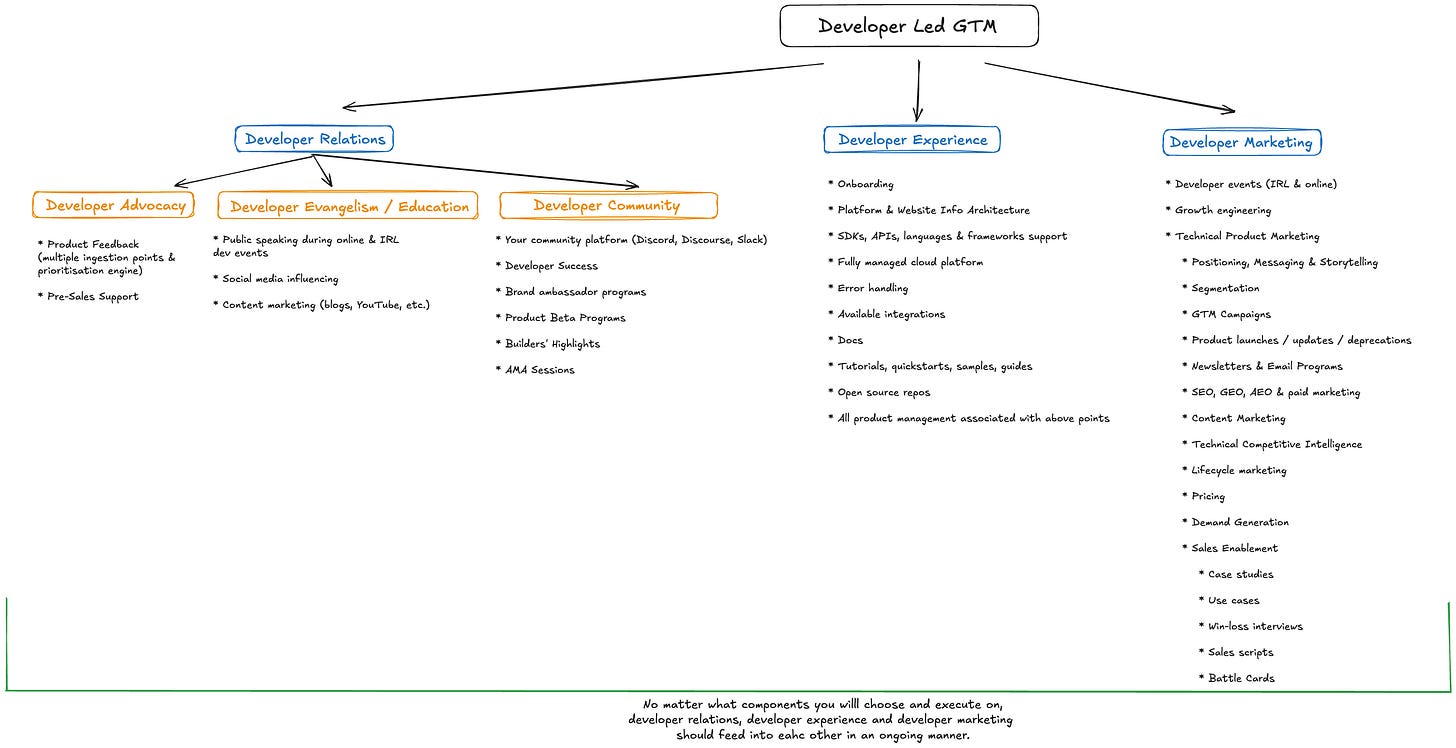

Before diving in, zoom in on the diagram. Its structure carries most of the argument.

Over the years I’ve seen countless attempts to define the “right” model for developer-focused companies. Each proposes a universal structure, a perfect alignment of teams, functions, and responsibilities. But there is no one-size-fits-all template. At best, you find patterns that resonate and frameworks that help you think more clearly.

For me, the model consistently distills into three core components:

Developer Relations

Developer Experience

Developer Marketing

This isn’t theory. It’s the product of a decade spent operating at the intersection of DevRel, product marketing, product management, and engineering, through both the wins and the failures. Could sales be a fourth pillar? Possibly. I haven’t operated inside that structure myself, so I’ve intentionally left it out. I’ll revisit it if experience ever proves it necessary.

Let’s break down what each component represents.

Developer Relations

People like to say that DevRel has already been fully defined, that by now, everything worth inventing has been invented. The same claim gets made about almost every field, and it’s always wrong. No discipline stops evolving, especially one as closely tied to engineering as DevRel.

The point isn’t to defend a specific definition. It’s to stay open to reframing it. If what follows challenges how you currently think about DevRel, that’s the intention. The goal is to broaden the context, not to preserve the status quo.

Developer Advocacy

At its core, Developer Advocacy is exactly what the name implies: advocating for developers. That begins with understanding the underlying needs behind the feedback they share, not just the literal request, but the problem it points to.

The role is to translate those needs accurately, internally and externally. Developers should know where their feedback goes, how it’s used, and when it influences the roadmap. That transparency creates trust, and trust encourages deeper, more meaningful feedback over time.

The principle is simple:

Represent developers’ interests in a way that directly shapes the product.

Developer Evangelism / Education

The purpose here is straightforward: help developers understand, adopt, and succeed with the product. Evangelism, stripped of its historical baggage, simply means sharing ideas, telling the story, and inspiring interest. Education builds on that by teaching the concepts, patterns, and technical foundations developers need to solve real problems.

The industry now uses “developer educator” more often than “evangelist,” but the underlying function hasn’t changed. Both exist to increase understanding, spark adoption, and expand the community of developers who know how to use the product well.

Developer Community

Community is ultimately built through consistent, meaningful interactions. Not relationships in the personal sense, but the professional ones that form when a developer feels supported, inspired, or unblocked by someone on your team. Most developers can recall a moment when an advocate, educator, or engineer from a company helped them solve a problem or showed them something new. Those moments compound. They create affinity and eventually, community.

The work spans a wide spectrum, from hands-on developer support and technical guidance, to highlighting what people are building, to AMAs and deeper conversations with the team, all the way to structured programs like champions or ambassadors.

The through line is simple:

Create spaces where developers can learn, share, build, and feel connected to the product and the people behind it.

Developer Experience

The term likely evolved from UX, adapted into the devtools space as products became more complex and the expectations of developers increased. Most people in the field have an intuitive sense of what DX means, but it’s worth articulating clearly.

Developer experience is about enabling developers to use the product correctly, efficiently, and ideally enjoyably. That experience starts long before anyone writes code. It begins with the first spark of interest, continues through learning and evaluation, and extends into purchase and building.

The goal is simple:

Optimize for developer clarity and developer joy across every part of the product surface.

Whether someone is interacting with a single component of your product OS or navigating across multiple parts of it, the experience should feel coherent, predictable, and effortless.

Developer Marketing

Despite how the diagram might initially read, Developer Marketing isn’t a promotional layer on top of the product.

It functions as the bridge between engineering and the developers who will ultimately use what you build. It is responsible for understanding the product deeply, translating its value clearly, and shaping the pathways through which developers discover, evaluate, and adopt it.

Developer Marketing is the force that gets a product to market and the discipline that ensures it stays relevant once it’s there.

The work spans multiple dimensions. It means crafting the narrative around why the product exists and the problems it solves. It means defining the entry points into the product OS, clarifying the mental models, and guiding developers toward the shortest path to “I understand this” and “I can use this.” It also means owning the signals that help a team know what’s working: documentation engagement, tutorial completion, SDK adoption, time-to-first-success.

At its best, Developer Marketing doesn’t feel like marketing. It feels like context: the explanations, examples, and guardrails that make a product approachable and usable. It aligns the internal story with the external one and gives developers the clarity they need to make a decision.

The goal is simple:

Connect product and developer in the most honest, efficient, and technically grounded way possible.

Components Choice

You may have noticed that the groups in this model share overlapping functions. That overlap is intentional. It doesn’t mean you can swap one component for another and expect identical outcomes. Sometimes that works, often it doesn’t. The execution, context, and maturity of the company make the difference.

So how do you decide which components to invest in, and when?

There’s no universal playbook. The right combination depends on factors that change from company to company: product maturity, business model, team structure, industry norms, and whether you’re operating like a startup or a large organization. The variables are too numerous and too dynamic for a static answer.

The only reliable approach is experimentation. Run small tests. Move quickly. Instrument your efforts so you can measure what improves the developer journey and what doesn’t. When something fails, pivot. When something works, repeat it until it no longer does.

Over time, you’ll identify patterns. The set of activities that consistently drive adoption, clarity, and activation for your product. But even then, the work doesn’t stop. The landscape keeps shifting, and the strategies that worked last year may lose their effectiveness without ongoing iteration.

The goal isn’t to find the perfect mix once.

It’s to continually refine the mix as the environment, product, and developers evolve.

The Principle

Developers rarely want a partial view of a solution. They want the full picture the context, the reasoning, the details that let them make informed decisions and build with confidence.

The takeaway is simple:

Upgrade your users, not just your product.

Give them the clarity, tools, and understanding needed to unlock the value you’ve created. When developers level up, the product does too.